Baroque Rebellion at the AGO: Jesse Mockrin and the Art of Feminine Agency

Through light, crop and intentional negative space, Mockrin challenges the stories surrounding women painted into obedience.

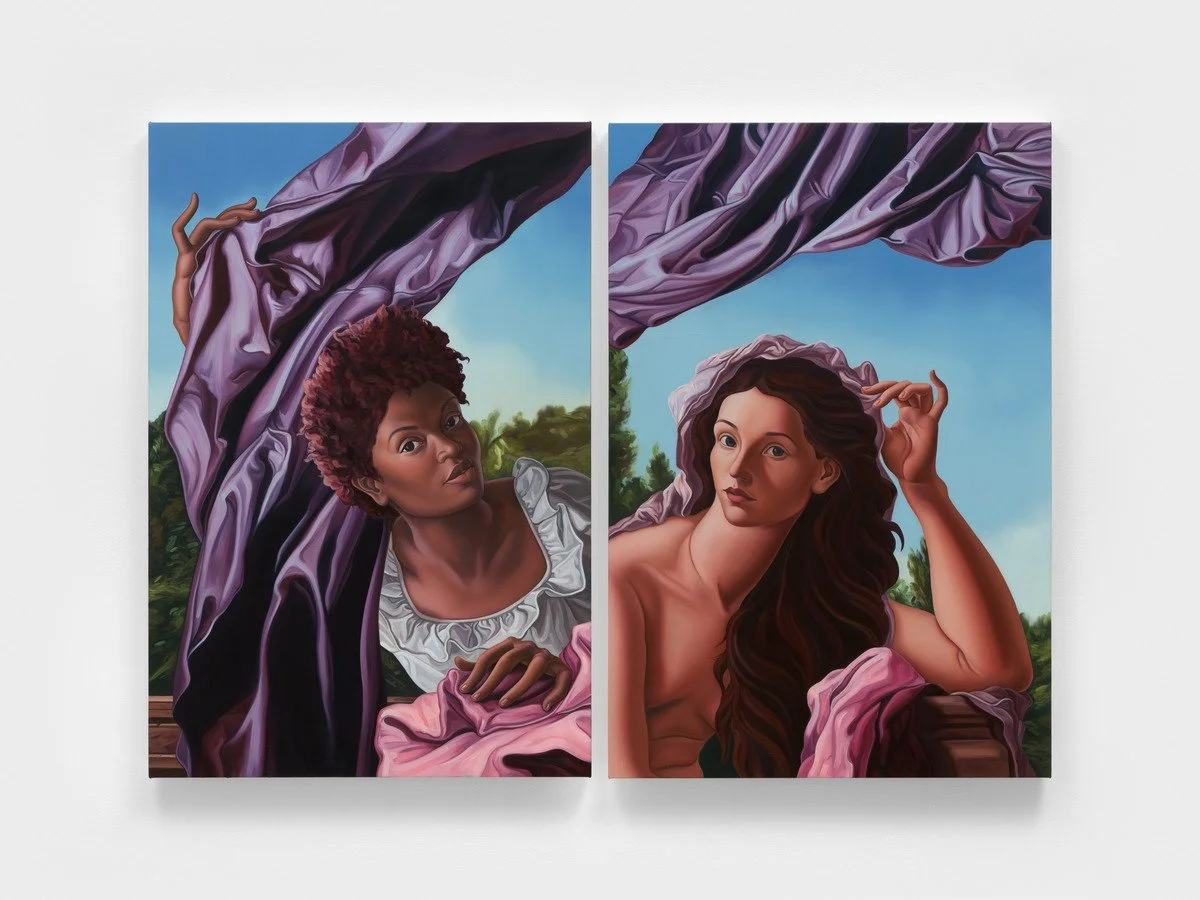

Photo Credit: Jesse Mockrin, Fracture, 2024

The gallery hums with the sound of breath held between centuries. Light pools against oil and linen, bending around bodies that seem to remember something the rest of us have forgotten. Jesse Mockrin’s paintings live in that hush — between devotion and defiance. Her brushwork recalls the chiaroscuro of the Baroque old-world, yet her vision belongs to the present.

Photo Credit: Jesse Mockrin, Billie Eilish, 2020

Mockrin’s breakout moment came in 2020 when her Baroque-style portrait of Billie Eilish captured international notoriety, a work that merged pop iconography with Caravaggio-inspired drama. The image went viral for its eerie serenity – a siren saint reborn in a hoodie. It marked the arrival of Mockrin’s unmistakable style: classical technique charged with contemporary subversion.

Now, five years later, Mockrin debuts Echo, an exhibit including 25 paintings and eight drawings at the Art Gallery of Ontario, on now until spring 2026. Echo feels both contemporary and timeless — a meditation on how myths around gendered violence persist beneath history’s gilded frame, until the story feels palpitably diluted, sneaking into our subconscious without setting off any alarms. Every canvas asks what moral survives when a story is told often enough to seem true. The work was three years in the making, realized in close collaboration with the AGO’s European Art department, its foundation drawn from Renaissance and Baroque paintings in the gallery’s own collection. “To study the past helps us to better understand the present,” Associate Curator Adam Harris Levine explains. “Historical paintings contain great beauty and tell us much about how we live today, but mask with their grandeur great violence. Mockrin draws our attention to these stories, because they offer insight into how and why society still expects women to be treated with cruelty.”

Mockrin’s subjects pull from Greek and Roman origin myths and biblical characters — Echo, Eve, Daphne, Mary Magdalene, the Sabine Women and more. These figures have long been bound to narratives of coercion and control. We’ve absorbed these myths as moral instruction without examining the violence that shapes them. Mockrin compels the viewer to look again, to look closer. She explores the concept of objectivity and the selective memory embedded in art history. “By liberating these figures from their original context, my hope is that I can empower the viewer to see these figures with empathy, and to see historical art anew,” Jesse Mockrin shared.

The exhibition begins with a piece centered on Mary Magdalene, presented as a fragmented collage. Mockrin splices her own painted imagery with archival photographs of women from Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries — workhouses that confined “fallen” women well into the late twentieth century. The juxtaposition is unsettling. Here, the viewer encounters the foundation of Mockrin’s research process, connecting biblical lore to modern institutions of gendered punishment. The room feels like confession without absolution. Levine noted, “Mockrin’s cropped compositions, here and throughout, mirror the violence of gender-based erasure itself — what version of the story is framed, and what is left out?”

The next gallery opens into scale. Large canvases, including Only Sound Remains, suspend their figures in a state of half-exit. Opposite hangs Judith, positioned beside a Baroque original from the AGO’s collection — a dialogue across centuries. Here, Mockrin’s mastery of oil painting shines. Her strategic use of light feels cinematic. In Only Sound Remains, she distills the myth of Echo to its psychic residue. The background disappears. The nymph’s outline floats in an undefined void, stripped of landscape and ornament. The absence of context queues becomes the point. This is not a retelling but a reimagining. In classical depictions, Echo is contextualized by the wilderness and the wrath of Hera. In Mockrin’s version, she exists in suspension — a gesture of longing without destination. The painting evokes the moment between sound and silence, grief and self-recognition. Mockrin’s theatrical framing highlights the familiar, only to remind us we never truly saw it before.

Photo Credit: Jesse Mockrin, Witness, 2025

Throughout Echo, hands emerge as their own language. Mockrin’s treatment of them borders on the surreal. They bend beyond natural capacity. They appear elegant yet unsettling, with joints that hyperextend in ways real fingers don’t. They are as beautiful as they are impossible. In another artist’s work, such distortion might signal error. In Mockrin’s, it is a thesis. These hands could not function in life, yet they are transcendent in art. They summarize her critique of beauty as both ideal and violent. The tradition of Mannerism — the post-Renaissance pursuit of elegance through exaggeration — is reborn here as a feminist allegory. The hands reach, grasp, twist … but never rest. They remind us of how beauty has long been used to aestheticize harm, to make the horrific appear divine.

Photo Credit: Jesse Mockrin, The Descent, 2024

In The Descent, a five-panel reimagining of The Abduction of the Sabine Women, Mockrin transforms a familiar historical tableau into something fractured and uneasy. The composition feels theatrical, yet its continuity collapses upon closer inspection. Figures nearly touch across the seams but never align. Human forms collide with horses. Limbs fragment and vanish at the frame’s edge. The disruption is intentional. What happens “off-stage” becomes more disturbing than what’s shown. This restraint calls back the sensibilities of the Baroque masters — Rubens, Bernini, Caravaggio — artists who blurred the line between art and theatre, who understood that drama often lives in what remains unseen. Mockrin reclaims that theatricality as critique. Her motion-filled compositions pulse with stagecraft.

The final room offers relief — or perhaps release. Here, the witch appears as a redemptive figure, a counter-myth to centuries of condemnation. She is rendered not as a threat, but as a healer. Mockrin also presents her first still life, Tribute, a bouquet of plants once used by women in mediaeval times to regulate fertility and manage wellness. She cultivated the herbs herself, cut them from her garden and painted them as an homage to Rachel Ruysch, the celebrated Dutch still life painter of the seventeenth century. At first, it seems a study in texture and tone, but beneath the petals lies a recurring theme of defiance: look closer, things aren’t always as they seem.

The witch is portrayed as archivist, as custodian of knowledge passed from woman to woman, surviving revisionist history that hides the ugly through behind a beautiful, bloody, facade.

This final room invites the viewer to imagine an alternate ending to all stories that have come before — one where agency and ancestry coexist.

Echo challenges what we thought we knew, or never really thought about at all. To stand before the works of Mockrin is to feel history breathing through new lungs.

Editor’s Note: For many women — myself included — this moment in history feels like a monumental threshold. We are the first generation of women in our families to hold genuine agency over our own lives, to decide the shape of our work, our bodies, our homes, our legacies. Though ownership and freedom remain unevenly distributed, the possibility itself is unprecedented.

Echo speaks to this hard won shift – the right to reclaim authorship of our stories.

If you can see Echo, go. Stand before the paintings and let them look back at you. There is something sacred in the way that Jesse Mockrin renders silence; a reckoning, a remembering. For every woman who has ever been reduced, rewritten or erased, this exhibition feels like recognition.

JESSE MOCKRIN: Echo

(Level 1, Philip B. Lind Gallery, AGO — On now)

Inspired by Baroque master works, Jesse Mockrin’s Echo reimagines historical and mythological subjects through a distinctly contemporary, feminist lens. Her cropped compositions and lush palette evoke the sensual and the uncanny—illuminating untold dramas buried in the art historical canon.

Hours: Tuesday–Sunday, 10:30 AM – 5 PM (open late Wednesdays until 9 PM).

Admission: Always free for AGO Members, Annual Passholders, Ontarians under 25, and Indigenous Peoples.

Art Gallery of Ontario, 317 Dundas Street West, Toronto.